-

Depression’s Spillover Effects: Living in a Household with an Adult with Depressive Symptoms

To the best of our knowledge, the economic and mental health effects on those living in the same household as a person with depressive symptoms have not been estimated in detail – until now.

Depression is a crippling and potentially recurrent condition, which can create a downward spiral in the ability to fulfill family, social, and work responsibilities. Previous studies have documented the severe consequences of depression on those living with it.

However, the economic and mental health impacts of living in the same household as an adult with depression have only been partially estimated to date, and prior research on such spillover effects has been focused primarily on caregivers.

Our research team sought to fill this knowledge gap by drawing upon the extensive, publicly available data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component (MEPS-HC). We used these self-reported data to examine the economic and quality of life (QoL) outcomes of adults without depressive symptoms living in “depression households” (i.e., households with an adult with depressive symptoms), and compare them with outcomes for adults living in “no-depression households” (i.e., households without an adult with depressive symptoms).

Below, we summarize some of our key findings.

Work-Life Balance and Economic Consequences

Previous research on the economic impact of depression has focused primarily on direct and indirect costs incurred by those with depression. In a 2023 study on the economic burden of depression based on 2019 data, we included estimates on the impact of depression on the income of household members. We found that this indirect component of the economic burden represented nearly a quarter (24%) of the total economic burden associated with depression.

Source: Greenberg P., et al. “The Economic Burden of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder in the United States (2019),” Advances in Therapy (2023)

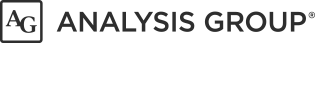

Generally, these results differ in composition but not overall magnitude from our past estimates of the economic burden of depression,1 with the differences being attributable to different underlying data sources.Our current findings also add further detail to work-related impacts of living with an adult with depressive symptoms on other household members without depressive symptoms. Overall, in addition to earning less in average annual income compared with their counterparts in no-depression households, these household members were less likely to be employed and had more missed workdays.

Medical Care and Health Care Resource Utilization (HRU)

Somewhat surprisingly, we found few significant differences in HRU or health care costs between adults without depressive symptoms living in depression households and those in no-depression households. These findings contrast with other studies, but we were not able to fully ascribe specific causes for the counterintuitive results in our current study. Potential contributing factors include underreporting of health care services and costs in the MEPS data.

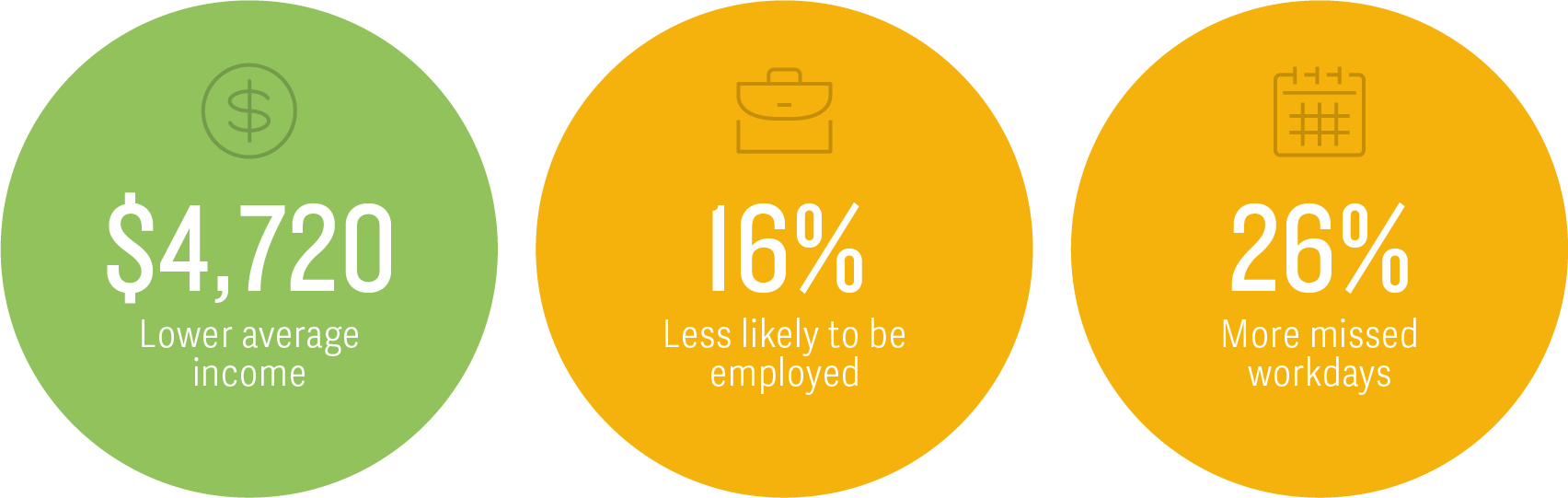

We did find that those living in depression households were 1.5 times more likely to have mental health–related outpatient visits than adults living in no-depression households. Previous research has described potential contagion effects of poor mental health on those living in close proximity.2

Quality of Life

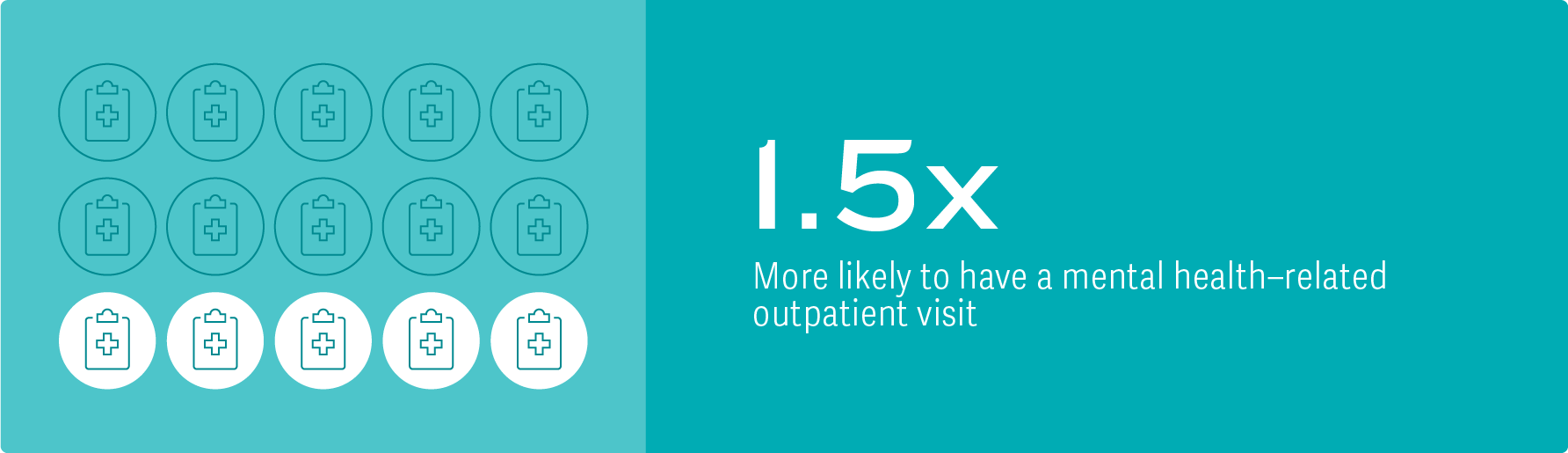

Finally, our study shows that living in a depression household can lead to worse QoL for other household members without depressive symptoms.

Other studies have suggested that living with individuals with depressive symptoms may impact QoL in a variety of ways,3 including:

- Restricting household members’ social and leisure activities

- Placing a financial burden on the family

- Putting considerable strain on marital relationships

- Causing household members to suffer from insomnia, worry about the future, and experience high levels of anxiety and depression

“Depressive symptoms such as sadness, irritability, social withdrawal, and lack of motivation, can create tension and conflict within the home.”– Greenberg, et al., 2024

“Household members may take on additional responsibilities, such as caring for children, completing household chores, or providing a stable source of income, which can cause strain and emotional distress, impacting daily routines and social activities.”– Greenberg, et al., 2024

Improved Support Could Help Alleviate the Burden

Overall, we believe our findings underscore a critical need for proper support of individuals with depressive symptoms, as well as their families and household members, regardless of whether those household members are caregivers or simply living with someone who experiences depressive symptoms. ■

“Programs and resources that help reduce the strain of balancing work and household roles, such as peer support groups and household-focused approaches to improve personal physical and mental health, may decrease the stress associated with living in a depression household and ultimately reduce the spillover effects observed in this study.”– Greenberg, et al., 2024

“Study findings emphasize the need to ensure patients with depressive symptoms are identified and receive appropriate intervention, as improved management could address the increasing prevalence of depressive disorder and alleviate the burden associated with depressive symptoms on the individual themselves as well as on the members of their household.”– Greenberg, et al., 2024

Paul E. Greenberg, Managing Principal

Andrée-Anne Fournier, Vice President

Patrick S. Gagnon, Vice President

Jessica Maitland, ManagerEndnotes

- Greenberg, P., et al. “The Economic Burden of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder in the United States (2010 and 2018).” PharmacoEconomics (2021).

- Eisenberg, D., et al. “Social contagion of mental health: evidence from college roommates.” Health Economics (2013).

- Katsuki, F., et al. “Multifamily psychoeducation for improvement of mental health among relatives of patients with major depressive disorder lasting more than one year: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial.” Trials (2014). Luciano, M., et al. “A ‘family affair’? The impact of family psychoeducational interventions on depression.” Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics (2012). Ware Jr., J., et al. “A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity.” Medical Care (1996).

Adapted from Greenberg, P., et al., “Impact of living with an adult with depressive symptoms among households in the United States,” Journal of Affective Disorders (2024)

-

Using Self-Reported Data to Estimate Economic and Social Impacts

The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component (MEPS-HC) uses in-person, computer-assisted interviews to collect detailed information from nationally representative samples of individuals and households in the US.

- MEPS-HC includes a well-validated depression screening tool, which we used to identify depression households and no-depression households.

- For both household categories, we analyzed the MEPS data on income, employment status, workdays missed, health care costs, and health care resource utilization.

- In addition, MEPS-HC includes a standard questionnaire for physical and mental health quality-of-life (QoL) measures. These are reported as summary scores for a physical component and for a mental component.

- The physical component covers physical functioning, physical limitations in usual role activities, bodily pain, and general health perceptions.

- The mental component covers vitality (energy and fatigue), social functioning, emotional limitations in usual role activities, and general mental health (psychological distress and well-being).

From Forum 2024.