-

Understanding Obesity: In Conversation with Professor John Cawley and Dr. Fatima Cody Stanford

Context from both economists and clinicians can illuminate decisions about treatments and costs associated with obesity and related conditions.

To provide that context, Analysis Group Principal Laura O'Laughlin and Vice President Nicholas Van Niel moderated a discussion between Professor John Cawley, a health economist with deep experience researching obesity, and Dr. Fatima Cody Stanford, a practicing physician and obesity-medicine scientist.

Professor Cawley – the Daniel Patrick Moynihan Chair in Public Policy at the Maxwell School of Citizenship & Public Affairs at Syracuse University – studies the economic causes and consequences of obesity as well as policies and interventions that aim to treat and prevent obesity. He is also the president-elect of the American Society of Health Economists (ASHEcon). Dr. Stanford – a physician at Massachusetts General Hospital and an associate professor of medicine and pediatrics at Harvard Medical School – specializes in nutrition, health care disparities, and weight-related health issues, including obesity treatment, diagnostic criteria, and social stigmas.

During their conversation, Professor Cawley and Dr. Stanford explored some of the complexities in studying obesity, how economics could be useful in such studies, and related considerations for health care practitioners, regulators, and payers.

How did each of you become interested in obesity research?

Fatima Cody Stanford: Associate Professor of Medicine and Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, and Physician in Medicine, Pediatrics, and Endocrinology, Massachusetts General Hospital

Dr. Stanford: My work in obesity research stems from recognizing how nutrition, policy, and equity are interconnected. Through my physician training and work as a public servant, I’ve focused on reframing obesity as a chronic disease that demands evidence-based and compassionate care. Recently, as part of the 2025 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, I helped to ensure that US nutrition recommendations reflect both scientific understanding and the lived experiences of patients from diverse backgrounds.

Professor Cawley: Early in my Ph.D. program, I became interested in risky behaviors and began exploring applications of Gary Becker and Kevin Murphy’s A Theory of Rational Addiction, which led me to a more general study of the economics of diet, physical activity, and obesity. I think it’s fascinating to study how people’s choices reflect their responses to incentives and their environments, and how those decisions affect their health or the health of others. That also led me to evaluate interventions designed to alter people’s choices through taxes, subsidies, information, or medical innovation.

Why is obesity such a complex disease to study?

Dr. Stanford: Clinically, it can’t be said that there’s a singular cause of obesity, and the consequences of having obesity can be dire. The study of this disease – and it’s a disease, let’s remember – should be nuanced and involve assessments of genetic, metabolic, environmental, and psychological factors, all interacting simultaneously.

Additionally, traditional measures like BMI [body mass index] oversimplify obesity and fail to capture physiological differences among patients, which could lead to negative outcomes for those patients. As an author of the recent Lancet Commission on the definition and diagnostic criteria of clinical obesity, I contributed to the development of a new framework that recognizes obesity as a chronic, systemic illness characterized by alterations in the function of tissues and organs due to excess adiposity. The commission recommends moving beyond BMI alone and encourages a more comprehensive assessment to guide clinical care and policy.

John Cawley: Daniel Patrick Moynihan Chair in Public Policy, Maxwell School of Citizenship & Public Affairs at Syracuse University

Professor Cawley: As Dr. Stanford alluded, the myriad factors that contribute to the development of obesity, including nutrition, physical activity, income, food prices, education, environmental exposure, genetics, and pharmaceutical prescriptions, must be evaluated holistically in the context of an individual’s daily behaviors.

And the standard measure for obesity is a limited one that ignores body composition entirely. Uncritical use of such traditional measures can lead to inaccurate assessments of the impacts of obesity across populations. Those assessments might then lead to ineffective treatment standards and suboptimal regulatory guidance.

Dr. Stanford: Professor Cawley rightly points out that numerous factors – biological, environmental, and social – can contribute to the development of obesity. Before going further, however, I’ll note that we should exercise caution when referencing patients with obesity. Beyond studying data about the disease, removing any stigma associated with it requires, as a first step, removing “obese” as a descriptor from our language in reference to patients. Patients are not obese. They have obesity.

With that in mind, this disease is one of the most pressing health care issues of our time. Since it’s a chronic disease with serious health impacts and can affect patients from an early age, there is some urgency in developing and prescribing treatments that can prevent patients from developing obesity across diverse geographic regions and populations.

The prevalence of patients with obesity is enough to call the disease a global epidemic. Therefore, it could be beneficial to initiate cross-disciplinary studies to help guide prevention, treatment, and policy efforts related to the disease and its associated conditions.

Professor Cawley: Because obesity is so complex, no one discipline has all the answers. To help share information and promote multidisciplinary research on obesity, I edited The Oxford Handbook of the Social Science of Obesity, a summary of how researchers across the full range of social science disciplines think about obesity, and lessons from their research. Each chapter was written by a top obesity researcher, sharing their conclusions in a manner that is accessible to all.

There are several things that economists can contribute to the research on obesity. As a social science discipline, it’s dedicated to studying why people make the decisions that they do. Economic theory, in particular, focuses on issues such as prices, taxes, information, and habits, while behavioral economics examines crucial issues such as impulsivity and temptation. Economics prioritizes estimating causal effects, not just correlations, and thus has a range of tools that can be used to estimate the causes of obesity and the effectiveness of various interventions to treat and prevent it.

Beginning in the 1960s, there was a steady and then a rapid increase in the prevalence of obesity. In just a few decades, obesity shifted from being a relatively uncommon condition to one that affects 40% of adults in the US. Understanding how incentives, market structures, and policies can be leveraged to address this shift has become a central question in my research.

What are some of the economic effects of the obesity epidemic?

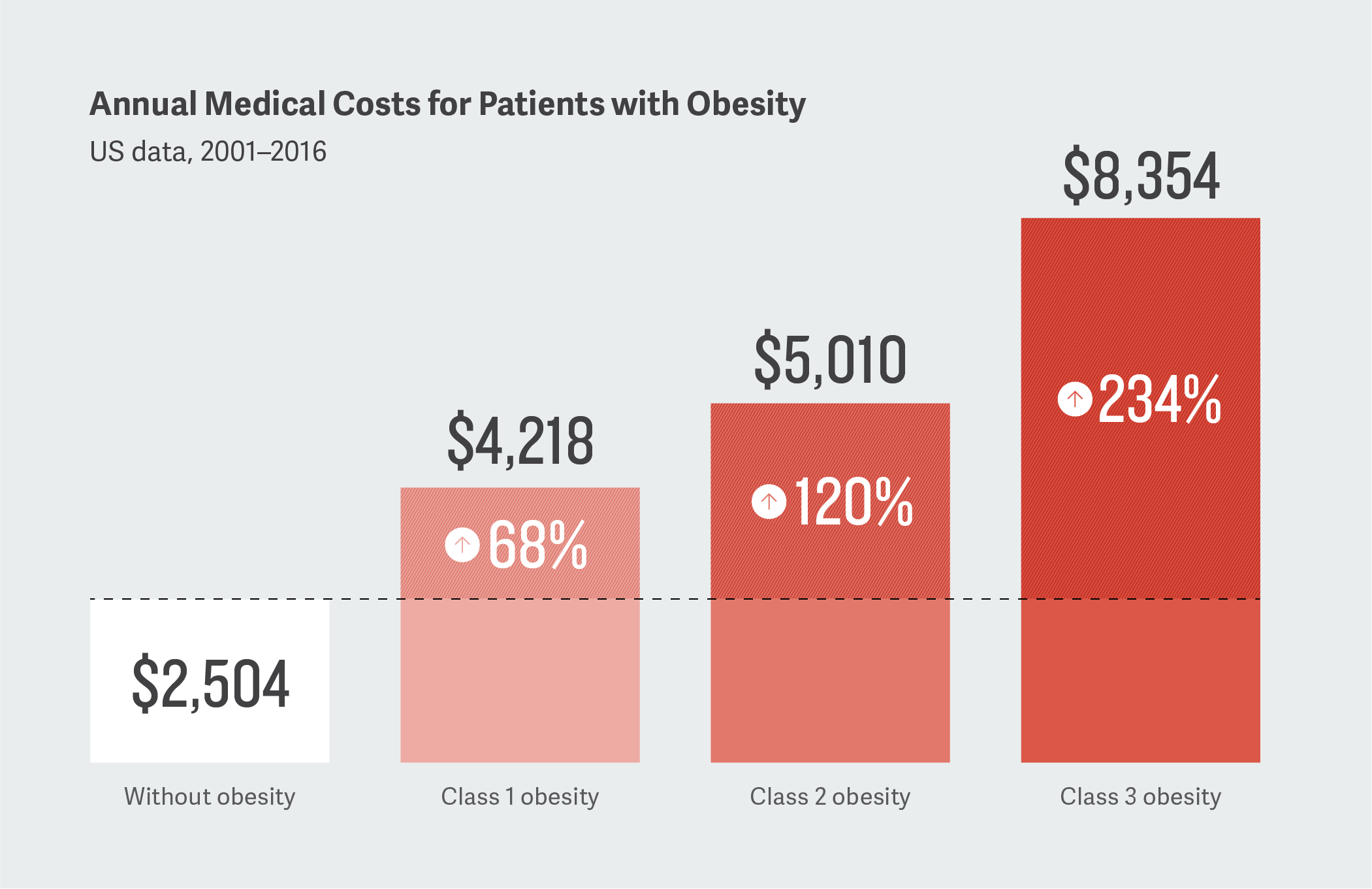

Professor Cawley: For one thing, there’s a substantial financial burden associated with obesity. In my research, I found that medical care costs tend to rise with excess weight, but they are particularly high among those with extreme obesity. These costs are across the board – higher expenditures on inpatient care, outpatient care, and prescription drugs.

The same is true for other costs like job absenteeism due to illness, which are especially high for those with extreme obesity. Understanding these costs illuminates the benefits of treatment and prevention, which are important in cost-effectiveness assessments.

And how could insights drawn from those frameworks affect patient care?

Dr. Stanford: The cost data you’re referring to are helpful to physicians like me to see financial impacts around patient care. For example, these data could help us address questions about inequitable access, insurance coverage, and drug pricing by shedding light on whether particular payer policies are effective for emerging treatments in specific patient populations. They might also highlight how broader socioeconomic factors, including systemic disparities and biases, can shape health outcomes. This kind of information can then be paired with clinical understanding to help reduce stigma and guide policy decisions.

When it comes to obesity, structural factors – such as poverty, food insecurity, and limited access to safe environments for physical activity – disproportionately affect low-income communities and communities of color, contributing to higher rates of obesity. Historical and ongoing underinvestment in these communities, as well as structural racism, have contributed to disparities in health outcomes and reduced access to resources that support health and wellness.

Additionally, weight bias and stigma can worsen health outcomes for individuals with obesity. Many people, including clinicians, assume that body weight is solely a matter of personal responsibility, overlooking the complex interplay of the factors that drive obesity. This can lead to miscommunication, reduced trust, and avoidance of health care, ultimately perpetuating health disparities.

Addressing obesity effectively requires a multifactorial approach that goes beyond individual behavior change. It involves recognizing and addressing the drivers of obesity, implementing evidence-based interventions in the communities most affected, and fostering compassionate, bias-aware clinical environments. By integrating these insights into clinical care and policy, we can more effectively reduce stigma, improve health equity, and support better outcomes for all patients living with obesity.

With that in mind, how can decision makers improve access to emerging treatments for patients with obesity while balancing concerns about affordability?

Dr. Stanford: In practice, it’s increasingly apparent that access is one of the central questions when it comes to considering emerging treatments for patients with obesity. Not only are injectables and tablets for treating obesity available to patients at a certain price point, but there are also technologies that can enhance a patient’s understanding of their own body and how a weight-loss program might work for them.

From new obesity medications to promising digital technologies such as continuous glucose monitors for people without diabetes, there have never been so many tools available to people hoping to lose weight. But access is still a problem. For instance, if I determine that a novel drug is best for my patient, an insurer may still deny coverage of that drug due to its high price point or perceived efficacy as compared to other, less expensive medicines. A holistic review of the value of treatments could better inform decision making regarding emerging therapies for obesity.

Professor Cawley: I agree completely with Dr. Stanford. Decisions about health insurance coverage and pricing should include an understanding of the value of a drug specific to the patient, as well as across populations of patients. And, when it comes to improving access and affordability to emerging treatments, evidence-based assessments of those treatments are vital.

To do that, clinicians, economists, and policymakers should collaborate to find the most appropriate and effective treatments for patients. Such an interdisciplinary approach could lead to effective and equitable solutions to the obesity epidemic. ■

This feature was published in January 2026.