-

When Code Becomes Evidence: Untangling Software and Algorithms in Litigation

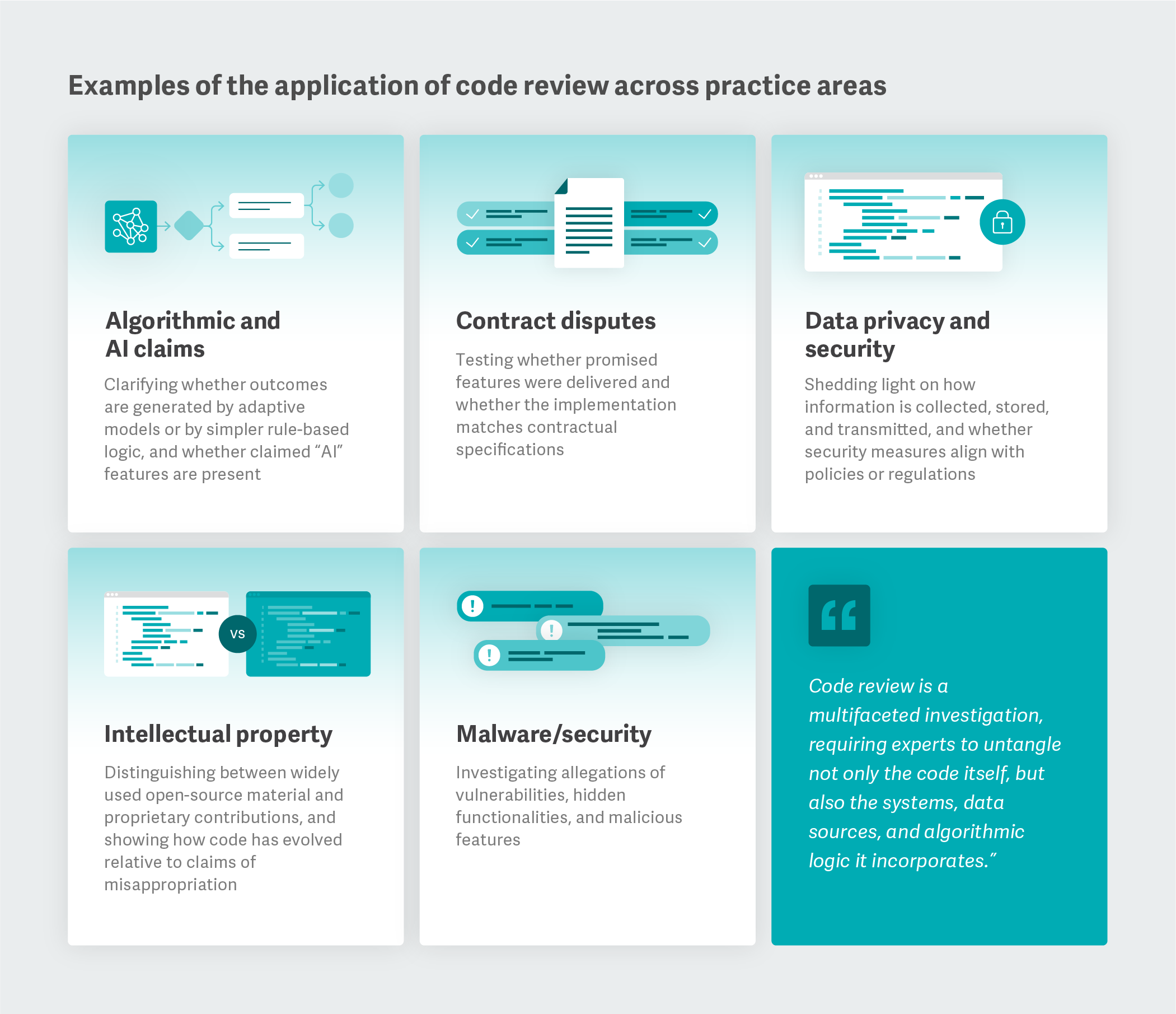

Code review is a crucial tool for establishing facts about software and algorithmic behavior.

Courts are increasingly asked to resolve disputes about software and algorithms, from traditional intellectual property and contract matters to newer claims about pricing tools, data handling, and AI functionality. As these disputes become more common, attorneys are relying on technical analysis to ground arguments in verifiable evidence. Code review can establish how software is designed to behave under relevant conditions, where data originate, and whether algorithms operate as claimed. It can also shed light on how code has changed over time and whether different implementations are meaningfully distinct.

Here’s a closer look at the evolution of code review, how it can be used across a variety of case types and practices, and the emerging challenges technology experts could face in future litigation.

The Process and Progression of Code Review

Decades ago, many software products were standalone commercial software, installed on one machine with a set number of files and a few hundred thousand lines of code. Now, codebases can span millions of lines, integrate a diverse set of technologies, and draw upon both custom-built and open-source components. They may automatically source data from external systems or run machine learning algorithms that change behavior depending on context. Code review is a multifaceted investigation, requiring experts to untangle not only the code itself, but also the systems, data sources, and algorithmic logic it incorporates.

Conducting code review in litigation begins with gathering the right materials. Depending on the case, this could mean gaining access to source code repositories, developer histories, system logs, and technical documentation. Access is sometimes provided in dedicated “code rooms” where experts are supervised and specific procedures are followed to access code and retrieve work product.

Code review itself can be done statically or dynamically. Static review involves examining the code structure without executing (running) the code. This is particularly valuable for understanding the core algorithms inside the code. Static review can reveal how the code is programmed to operate, the types of algorithms used (e.g., AI), and the various modules and components that make up the code, such as open source code.

Dynamic review involves running software, code, or both in controlled environments to reveal how it behaves under relevant conditions. While not necessary in all instances, this testing can uncover emergent behaviors that aren’t obvious from reading source code alone, particularly in complex systems with multiple interacting components such as digital marketing pixels. It can also help demonstrate how various users may be treated differently by the software – for example, the data flows related to individuals may differ based on device, settings, or web browser.

There is also version control analysis, which examines the code development logs created in the usual course by developers to trace when specific features were added, modified, or removed. This can be critical in determining what functionality existed during disputed periods. Software planning records can also be used to evaluate what features were planned and whether they were built as expected.

Regardless of review method, evidence is most effective when it is explained clearly. Technical experts develop demonstratives that tie their analyses back to the legal questions at stake, ensuring that complex technical evidence becomes accessible to non-technical audiences.

Emerging Challenges of Code Review and Litigation

Code review faces new hurdles as software becomes increasingly complex.

Companies are using – or claiming to use – more sophisticated algorithms to provide benefits to customers. Questions around what an algorithm is doing are increasingly asked in the context of AI recommendations, for example. Code reviewers are often being asked to disentangle which marketing claims are real, and what data sources are being used when making a recommendation.

In addition, complexity increases as generative AI systems enter business processes. Unlike traditional algorithms, AI systems can exhibit emergent behaviors that weren’t explicitly programmed. In some matters, this may increase the value of dynamic review and running tests to operate the system under a variety of inputs and prompts.

The data systems of today can also work across many different parties and systems. Data flows can come from a myriad of devices, pass through a variety of services, and be stored in databases either on premise or in the cloud. These transfers are orchestrated by code that can live on a variety of devices, which may be studied together to understand the full picture.

But the fundamental disciplines of code review remain constant: Rigorously evaluate the code to determine what it actually does. Verify that the code functions the way it purports to; don’t rely on claims about what it should do. When it’s time to communicate the findings of a review, ensure that the takeaways are comprehensive but also understandable for a broad audience. As software systems grow more complex and algorithmic decision making draws increasing scrutiny, these measures will only become more critical for resolving disputes where technology meets the law. ■

Mihran Yenikomshian, Managing Principal

Christopher Llop, Vice President

From Forum 2026.