-

If You Build It, Will They Come? Indirect Network Effects and the “Chicken-or-Egg” Dilemma in the Nascent Electric Vehicle Market

Will equitable electric vehicle (EV) adoption occur without a widely accessible charging network? Public policy could have an important role in boosting the nascent EV market into a self-reinforcing cycle of growth.

Policymakers view electric vehicles (EVs) as the primary pathway to reducing carbon emissions from the light-duty vehicle market. Yet the US market for EVs, which are touted for their broadly appealing societal, environmental, and cost benefits, is still in the early stages of its development. As a still-developing two-sided market, it is at a critical crossroads: There is no guarantee that a publicly accessible EV charging network will materialize to support EV adoption across a wide range of demographic groups and income levels.

For this reason, public support for charging network investment can help assure consumers that accessing EV charging will be convenient and reliable. By providing the right incentives, policy may help jumpstart charging network investment to meet the needs of consumers in an equitable fashion, and with a focus on maximizing the societal and environmental advantages of EVs.

Where Are We Starting From?

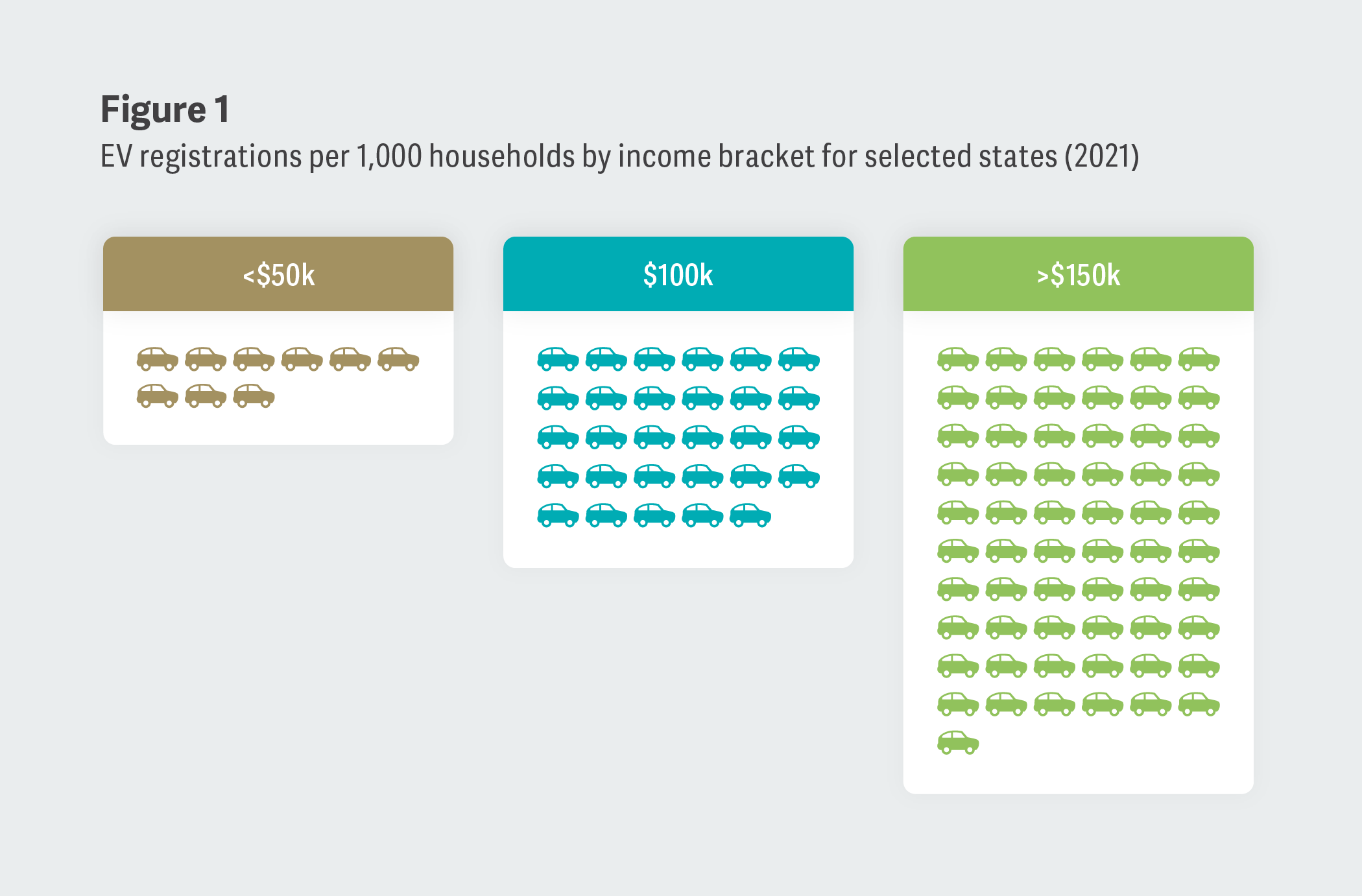

The federal government and an increasing number of US states have enacted legislation that envisions millions of EVs on the road by 2030. However, as of 2021, EV adoption in selected states with legislation or policies supporting EVs was concentrated disproportionately in higher-income communities. (See Figure 1.)

Note: Data were calculated by ZIP Code income. States included are CA, CO, MN, MD, NY, OR, and WA.

Note: Data were calculated by ZIP Code income. States included are CA, CO, MN, MD, NY, OR, and WA.

Sources: [1] https://data.census.gov/table; [2] https://www.atlasevhub.com/materials/state-ev-registration-data/; [3] https://udsmapper.org/zip-code-to-zcta-crosswalk/; [4] https://www.energy.ca.gov/files/zev-and-infrastructure-stats-dataSeveral factors contribute to disproportionate adoption among high-income households. Although EV prices have continued to decline, early EVs tended to have higher purchase prices than conventional vehicles. High-income households were more likely to own multiple vehicles, allowing them to adopt an EV while retaining a gasoline-powered alternative for long trips. And high-income households are more likely to be homeowners and to live in single-family housing that has dedicated parking, making recharging easy.

To achieve nationwide EV adoption goals, consumers across a broad range of income levels must be able to purchase and fuel EVs. For consumers without easy access to at-home charging, this will require access to reliable and convenient public charging stations.

The Decisive Factor: Indirect Network Effects

Characteristically for a two-sided market, EV market growth relies on the ability to develop both sides of the market simultaneously. Specifically, EV adoption (particularly for households that don’t have a way to easily charge at home) requires convenient access to fast, reliable charging stations. But private developers of charging stations evaluate their investments based on expected return on the investment, which itself is driven by demand of EV owners.

This is the classic “chicken-or-egg” problem that characterizes two-sided markets relying on indirect network effects to “tip” the market into self-sustaining profitability. Indirect network effects – or the feedback loop whereby value on either side of the market impacts value on the other side – can either boost self-reinforcing growth, or slow initial growth and create potential inefficiency if users wait to adopt the new technology.

Thus, if the number of charging hubs increases, EVs become more attractive to own or lease, leading to more EVs on the road and the increased profitability of charging hubs. (See Figure 2.) Higher profits lead to further charging hub investments. This feedback effect builds on itself and can drive organic growth in both charging hubs and the number of EVs.

The growth of digital platforms offers many examples of how these feedback effects can drive rapid adoption. But such growth cannot simply be taken for granted.

The new EV market may still “stall out” at a low level of adoption if charging hub operators don’t have a strong enough profit motive to build out the network. If consumers in lower-income communities are slow to adopt EVs due to high upfront costs or concerns over the availability of convenient public charging infrastructure, and infrastructure developers won’t build charging stations unless the demand justifies it, then the benefits of state programs to incentivize equitable EV adoption across a wide range of communities are unlikely to be realized.

How an Expanding Network Can Expand the Entire Market

It is natural to think of competition between different companies as a zero-sum game, where one firm’s gain is another firm’s loss. In many mature markets, this can be a plausible assumption. For instance, if a new supermarket enters a saturated market and attracts customers, the customers for the entrant were previously customers of the incumbent firms. Here, profit enjoyed by the entrant comes at the expense of the incumbents.

However, if the entrant attracted new customers who did not buy from a supermarket before, these new customers would not come at the cost of competitors. Rather, the entrant grows demand, increasing the size of the market overall.

Similarly, if a company builds public charging stations that expand the charging network, and the growing network induces new EV purchases, those newly purchased EVs can create benefits for both the new and old charging hubs.

Here, the zero-sum intuition about new entry into a market breaks down because as the charging network expands, it facilitates EV adoption and increases demand for the product.

An Important Role for Policymakers in Incentivizing Growth

Although adoption of EVs and charging stations has increased substantially over the past decade, progress has not been even across states, and the US still has a long way to go to reach the ambitious target of widespread adoption. A sampling of states (Figure 3) shows that ownership rates and charging infrastructure vary widely across states.

But even in the most forward states, EV adoption and charging infrastructure are still well behind levels in more mature marketplaces. As one example, Norway has roughly five times as many electric vehicles and charging stations on the road (measured in per capita terms) as California, the state at the leading edge in the US.

Source: Direct Testimony of Erich J. Muehlegger on Behalf of Northern States Power Company, December 19, 2022, MPUC Docket No. E002/M-22-432

Source: Direct Testimony of Erich J. Muehlegger on Behalf of Northern States Power Company, December 19, 2022, MPUC Docket No. E002/M-22-432For other states, needed levels of growth are more dramatic.

To achieve widespread adoption, policy will be needed to ensure charging stations are built out, not only in locations where EV adoption is already robust, but also in locations where EV adoption might occur more slowly. All else equal, private firms will prioritize locations with robust demand, as these locations will be the areas that are most profitable to serve. But in the US, areas where the highest number of EVs are registered are not representative of the overall population.

The $2.5 billion in subsidies offered as part of the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) reflects a step in this direction, specifically targeting charging station infrastructure in underserved and rural communities. Providing a platform for consumers from all income levels to be able to own and charge EVs is crucial for meeting socially driven decarbonization objectives and profit-driven market objectives. ■

-

Erich Muehlegger, Professor of Economics, University of California, Davis

Joseph Cavicchi, Vice President

From Forum 2023.