-

“Similar” but Not the Same:

Charting the Course of Biosimilar IP Litigation in the USSignificant differences in the manufacturing, regulation, and economics of generic drugs and biosimilars will mean differences in how IP litigation for biosimilars plays out.

Biosimilars are close analogues to brand or reference biologic drugs; both biosimilars and biologics are produced through a complex process of culturing living cells, rather than through chemical formulation. Biosimilar competition in the US is still in its infancy. The first biosimilar drug was approved in March 2015, and as of April 2019, only 19 had been approved. Yet there are approximately 70 additional biosimilars in the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) Biosimilar Product Development Program, with additional applications under review.

Intellectual property (IP) litigation surrounding biosimilars is also in its early stages. However, with biologic drugs now comprising the bulk of the highest-revenue drugs in the US, it is likely to continue to grow.

In trying to discern how litigation might unfold in the future, it is natural to look to the more familiar experience of the introduction of generic versions of small-molecule drugs, which are manufactured with chemical processes. Yet significant differences exist between small-molecule and biologic drugs, and these differences will affect how future IP conflicts are litigated.

In contrast to the straightforward method of chemical synthesis by which small-molecule drugs are produced, the greater complexity of both the manufacturing process and the resulting molecular structure of biologic drugs has three key consequences:

- Biologics and small-molecule drugs are subject to different approval and regulatory structures.

- A narrowly defined manufacturing process is required to maintain the safety and efficacy findings for the brand biologic from batch to batch.

- The brand biologic manufacturing process tends to be protected by a wider array of patents and trade secrets.

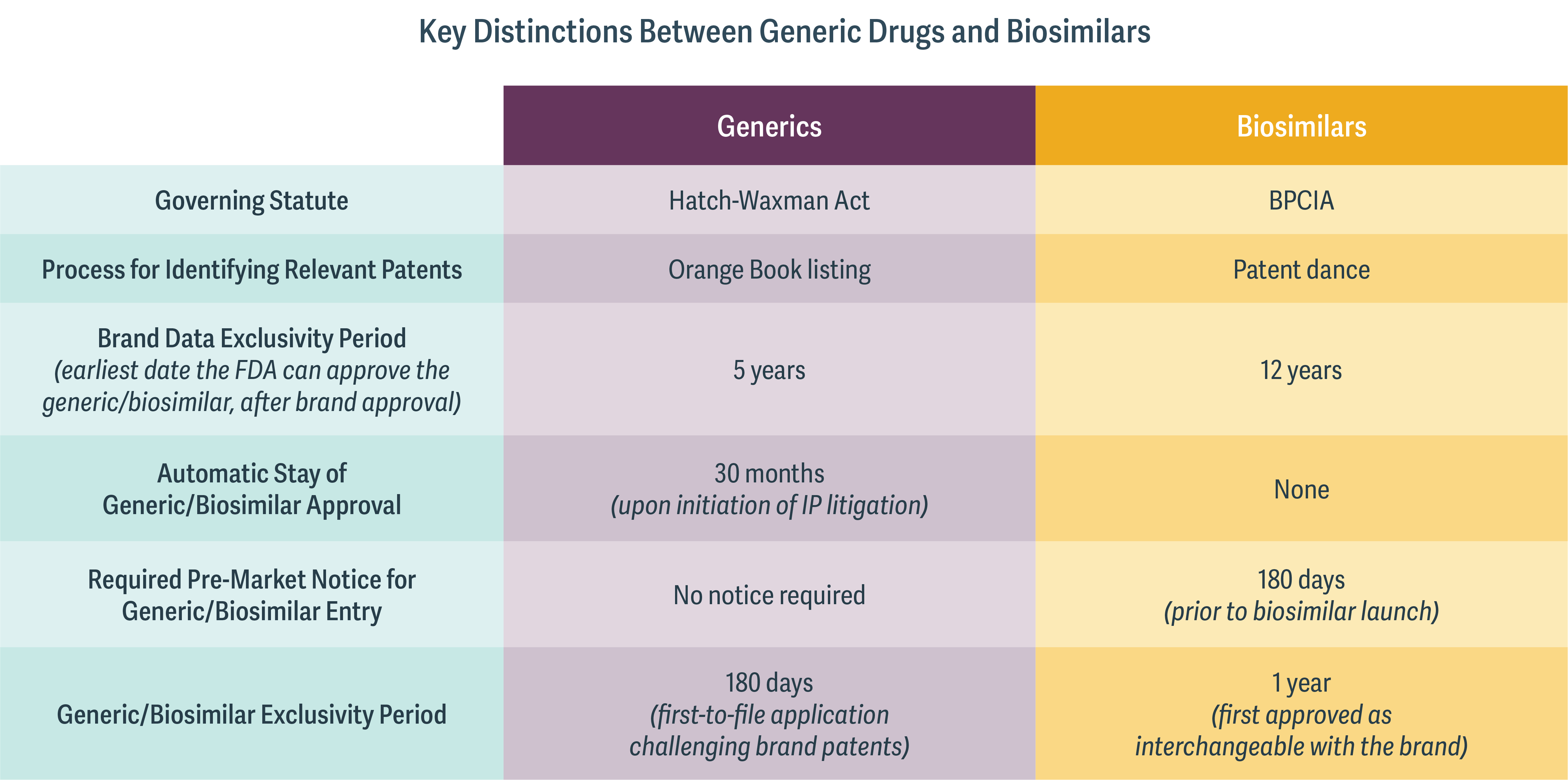

This is why the two different kinds of drugs are governed by very different IP regimes. (See table.)

Significantly, the respective processes for identifying the patents relevant to potential IP litigation are wholly dissimilar. For generic drugs, the relevant patents are listed in the so-called Orange Book, which provides a straightforward process for identifying patents at issue. Because of the more complex array of patents pertaining to biologic drugs, however, there is no corollary to the Orange Book. Instead, the relevant statute – the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) – sets out a process by which the biologic and biosimilar manufacturers exchange information on their respective technologies to determine which patents may be at issue in the first phase of litigation. This process is known as the “patent dance,” and even this process, the US Supreme Court held in 2017, is not mandated by the BPCIA.

The upshot is that the more complex technologies associated with biologic and biosimilar development give rise to a less transparent structure for identifying the IP relevant to the potential litigation.

In addition, the duration of exclusivity periods is different for small-molecule and biologic drugs. Many brand small-molecule drugs receive a five-year data exclusivity period, while many brand biologics receive a 12-year period. However, biosimilar manufacturers are allowed to file their applications after only four years, potentially allowing for eight years to resolve IP disputes prior to expiry of the brand biologic data exclusivity period. Biosimilar manufacturers may have strong incentives to challenge IP for the brand biologic early in an attempt to resolve IP litigation and accelerate entry soon after the brand loses exclusivity.

Finally, the BPCIA requires the biosimilar manufacturer to provide a 180-day “pre-market notice” before selling the biosimilar product. If the pre-market notice is made while the IP litigation is ongoing, it may signal an intended at-risk launch for the biosimilar. At that time, the brand biologic manufacturer is free to assert additional patents that may not have been agreed to in the “patent dance,” and may file for an injunction against the launch of the biosimilar.

The economics of biosimilar entry also differ substantially from those of generic entry. While biosimilars may capture a smaller share of sales from the brand than do generics, the limited entry of competing biosimilars and correspondingly modest price discounts may allow for greater gross profits. This may also encourage biosimilar manufacturers to launch their products at-risk – that is, while IP litigation is still ongoing.

From a practical perspective, then, a biosimilar manufacturer may deem it necessary to challenge brand biologic patents in order to successfully enter the market. However, the complexity of the patent array also makes it challenging for a biosimilar manufacturer to assess the likelihood that it will prevail in the IP litigation, as well as difficult to assess the risk from exposure to damages, should the biosimilar lose.

Perhaps for these reasons, the course of biosimilar IP litigation to date has differed substantially across cases. Decisions have varied on whether or not to participate in the patent dance, launch at-risk, settle IP litigation, and pursue antitrust litigation. Even the same manufacturer has pursued different strategies for different biosimilars. In the case of Zarxio, Sandoz chose to forgo the patent dance and launch Zarxio at-risk, at the time leaving open the potential for follow-on litigation had Amgen’s patents on Neupogen been upheld and had Sandoz been found to have infringed on those patents. With Erelzi, on the other hand, Sandoz chose to engage in the patent dance, and also agreed to a consent preliminary injunction that enjoins it from launching Erelzi while patent litigation is ongoing.

While the future prospects for this area of IP litigation are thus unclear, a sure grasp of the similarities and distinctions between generics and biosimilars will be critical for attorneys and economists working in this space. ■

Richard A. Mortimer, Principal

Brian Ellman, PrincipalAdapted from “The Rise of Biosimilars and the Future of Healthcare Intellectual Property” by Richard Mortimer and Brian Ellman, IAM, November/December 2018.