-

The Economic Burden of Depression: Finding Hope Amid Despair

Major depressive disorder, or MDD, is one of the most burdensome illnesses globally, to patients, employers, payers, and society. However, researchers are often challenged by the complex and varied clinical presentations of the disease.

For the past 30 years, I have led research teams at Analysis Group studying the economic burden of US adults with MDD. Our broad focus on people with depression has always been deliberate, as it brings to light more than just the medical treatment costs of depression-related hospital services, doctor visits, and antidepressant drugs. This approach also includes explicit attention to the societal burden that accrues from comorbid physical and psychiatric illnesses, the impairment in workplace productivity attributable to depression, and the economic impact of depression-related suicides.

Over the years, we have published periodic updates of our findings. The most recent update, based on 2018 data, appeared in a special edition of PharmacoEconomics, for which I also served as guest editor along with my research colleague and coauthor, Senior Advisor Tammy Sisitsky.

Our 2018 update, along with the other papers in this collection, shows how resource use, cost, and clinical outcomes vary widely among subgroups. We hope that our latest findings will be used by health care researchers and policy makers to identify, characterize, and address the needs of key subpopulations more effectively.

Key insights from Analysis Group’s research published in the special edition are highlighted below.

1. Depression Is Becoming More Widespread, Especially Among Younger Adults

From 2010 to 2018, the total number of US adults with MDD grew to 17.5 million, nearly a 13% increase. But for the first time in 30 years, in 2018 we found that nearly half of this total comprised 18–34 year-olds. This represents an increase from slightly more than one-third of all depression sufferers in 2010.

Unlike major physical disorders such as cancer or heart disease that tend to become more prevalent with age, the first episode of depression often occurs during the teenage or young adult years, when people are particularly vulnerable to long-lasting adverse consequences.

It is noteworthy that the two youngest cohorts also bore much larger shares of total incremental costs in 2018 than they did in 2010. (Incremental costs are the additional costs associated with a diagnosis of MDD.)

2. Direct Medical Costs Are Just the Tip of the Iceberg

We estimated that the economic burden of illness was $326 billion in 2018, but medical costs to treat depression accounted for only 11% of that total. In fact, for every dollar spent on inpatient, outpatient, and pharmaceutical treatment of depression, the societal costs for lost workplace productivity (absenteeism and presenteeism), treatment of comorbid conditions, and depression-related suicide amounted to nearly $8.

3. AI Tools Can Help Identify Meaningful Differences in Smaller Clusters of MDD Patients

For PharmacoEconomics, I worked with two of my colleagues, Principal Dave Nellesen and Manager David Proudman, to coauthor an overview of the 10 studies published in the special edition. There, we wrote:

“A consistent trend over the past two decades in the analysis of health economic and outcomes data has been an increased focus on various key patient subgroups, highlighting the heterogeneity of patient experiences with MDD.”

Many different factors, such as cancer status, comorbid conditions, age, and type of depression, can influence treatment decisions and the economic costs of the disease. However, identifying relevant subgroups using traditional approaches, such as clustering patients based solely on a clinical consensus, can be challenging in light of the increased complexity and evolving clinical manifestations of the disease.

Now, researchers can turn to the field of artificial intelligence (AI) for new tools that help them discern meaningful patterns and relationships in highly heterogenous populations.

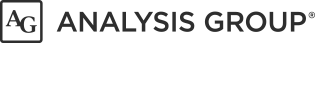

For example, in their study of patients with MDD and acute suicidal ideation or behavior (MDSI), researchers from Analysis Group and Janssen Scientific Affairs analyzed data using hierarchical clustering – an unsupervised machine learning technique – to group the study population into distinct clusters based on different combinations of patient characteristics.

This allowed the researchers to identify three clusters exhibiting meaningful differences in the ways that patients interacted with the health care system. For example, the clusters showed distinct differences with each other in terms of whether patients had been seen by mental health professionals before their suicidal episodes.

This data-driven approach to clustering led to the finding that those least exposed to health care before the index event continued to receive the least amount of care after it, highlighting the importance of continuity and quality of care among these patients with MDSI.4. Depression Treatment Still Is Not as Widely Accessed as It Needs to Be

Although the treatment rate has doubled over the past 30 years, it has remained stuck at around 56% for more than a decade. This suggests that some significant barriers to effective outreach remain, such as stigmatization of mental illness in society; lack of realization among depressed people that they need care; and a belief that treatment would work too slowly, not at all, or have adverse side effects.

With 44% of MDD sufferers not reached at all by the health care sector, a substantial unmet treatment need still exists. Reducing the economic burden of MDD will only be possible with more widely accessed and effective treatment.

Of course, we had concluded our research just before the COVID-19 pandemic hit in full force. Although the effects of the pandemic on depression are not yet well understood, some early hints point to the enormity of the problem that is now unfolding. In its Household Pulse Survey, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported an unprecedented increase in the rate of depression since just prior to the start of the pandemic. The overall prevalence has gone from 7% to 27% of the adult population, while it has gone from 11% to 39% for those in their late teens and twenties.

These staggering increases have resulted in depression prevalence levels far exceeding anything experienced before. As a result, we are now in entirely uncharted territory from the perspective of gauging the full burden of the disease. ■

From the Introduction to the Special Issue of PharmacoEconomics on Major Depressive Disorders

“We could not have known in late 2019 or early 2020 the level of devastation about to be caused by the once-in-a-century pandemic and resulting economic shutdown. The effects of the combination of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and the policy measures designed to limit both its spread and the severity of its adverse medical consequences has been staggering. One particularly striking change relative to the pre-pandemic period summarizes the enormity of the problem in this new era. In 2019, the US Centers for Disease Control estimated that the US prevalence of MDD was approximately 7%, and this skyrocketed to 27% during the pandemic. This stunning new reality has no obvious precedent in terms of the sudden spike in magnitude that will also endure for quite a while.

It is not clear how these fundamental changes in the prevalence landscape will affect the economic consequences of MDD. Will there be an accompanying tripling or quadrupling of the economic burden? How will treatment rates adjust, and what will be the role of new treatment approaches (e.g., telemedicine, smart phone apps)? For people who have been able to work from home during the pandemic, is the longstanding distinction between absenteeism and presenteeism still meaningful, and, if not, how should we think about indirect costs in the workplace when many people with MDD now work from home? For people whose first episode of MDD occurred during the pandemic, how enduring will their economic burden be once the pandemic retreats as a cataclysmic public health concern? These topics are so new that it will take several years to amass relevant data that can shine a bright light on their complicated dynamics.”

–Paul E. Greenberg and Tammy Sisitsky

Paul E. Greenberg, Managing PrincipalSources

- Cluster Analysis of Care Pathways in Adults with Major Depressive Disorder with Acute Suicidal Ideation or Behavior in the USA

- The Economic Burden of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder in the United States (2010 and 2018)

- The Growing Burden of Major Depressive Disorders (MDD): Implications for Researchers and Policy Makers