-

The Biosimilar Revolution Is Just Beginning in the US

The entry of biosimilars to the US market is still in its infancy, but their potential for widespread introduction represents one of the most significant events to hit the drug industry in decades, with many top-selling biologic drugs expected to be affected over the next few years.

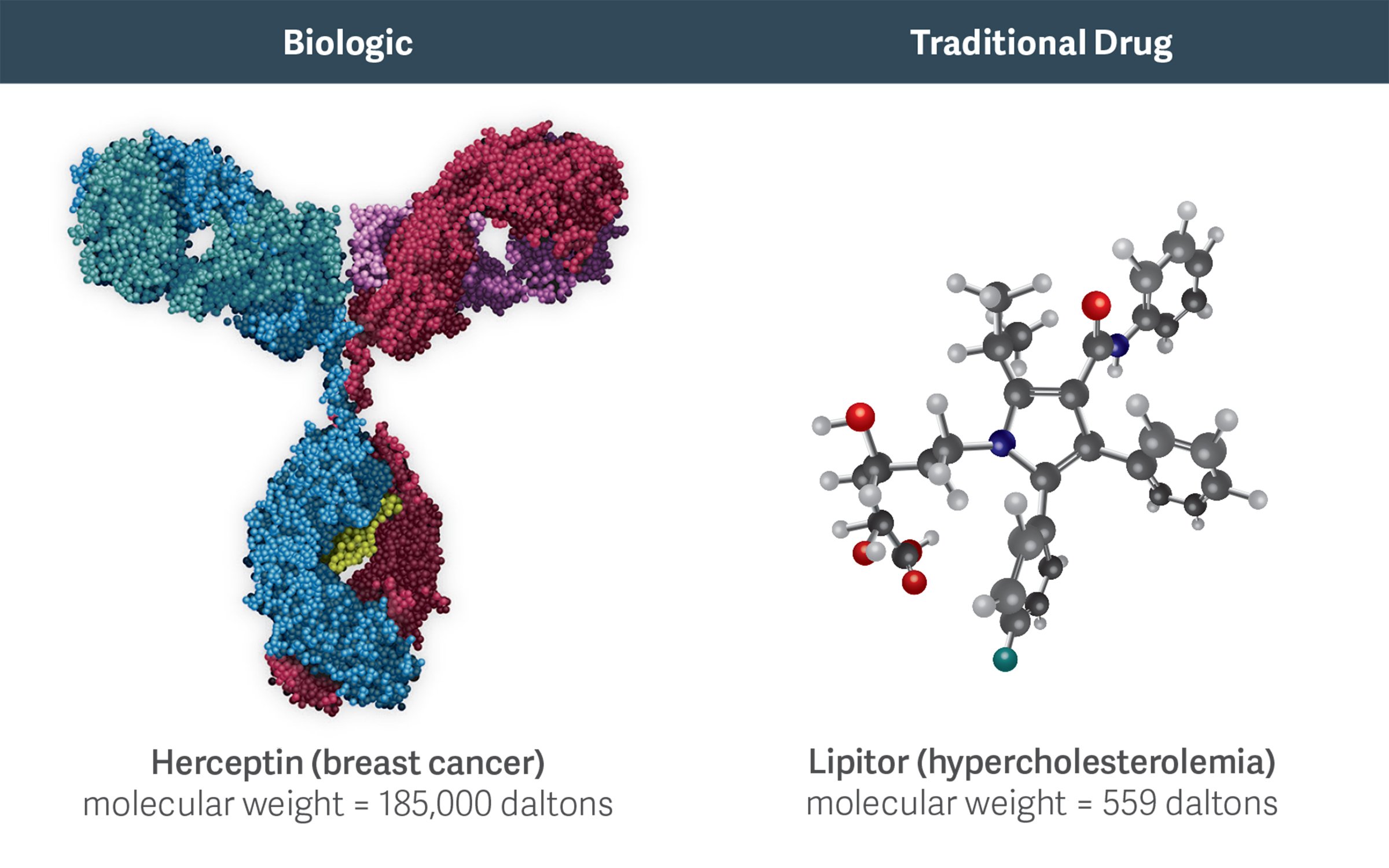

High molecular weight biologics like Herceptin are more complex than traditional, small-molecule chemical drugs like Lipitor. This complexity increases the costs, challenges, and risks of developing and manufacturing biosimilars.

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2009 paved the way for biosimilar entry, and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Biosimilar Product Development Program currently includes more than 50 biosimilars, referencing more than 15 different innovative biologics. To date, four of those biosimilars have been approved:

- Zarxio (brand reference product Neupogen) in March 2015

- Inflectra (brand reference product Remicade) in April 2016

- Erelzi (brand reference product Enbrel) in August 2016

- Amjevita (brand reference product Humira) in September 2016

The global market for biologic drugs has been forecast to exceed $390 billion annually by 2020, and some analysts predict substantial cost savings after more biosimilars are approved and introduced, as was the case with the introduction of generics. Indeed, one goal of the BPCIA was to try to achieve the level of cost savings realized from the widespread adoption of generics.

However, the development and approval processes for biosimilars, which are large-molecule biologics, are very different from those for generics, which are small-molecule chemical drugs. Consequently, biosimilar competition may share more features with traditional brand-brand drug competition than with brand-generic competition. In fact, the high costs of development (e.g., the FDA requires costly Phase III trials to approve a biosimilar) and manufacturing for biosimilars are likely to limit entry to a relatively small number of competitors, in contrast to the experience with small-molecule generics.

For example, based on the limited experience of biosimilar entries to date, penetration rates may be much more modest than for generics, and the price discounts may be substantially less. Research by Duke University Professor Emeritus Henry Grabowski and his co-authors at Analysis Group found that branded small-molecule drugs facing generic entry lose, on average, in excess of 75 percent of their sales within six months. In addition, generic price discounts average more than 40 percent relative to the brand’s price.

The share capture and price discount achieved six months after the introduction of Zarxio, however, have been much lower. The branded drug Neupogen lost only about 10 percent of its share, and Zarxio’s price discount was 15 percent. This is consistent with the experience following the earlier entrance of Granix, a quasi-biosimilar.

(See table.)Comparison of US Biosimilar and Generic Drug Average Share of Sales and Price Discount (Six Months After Launch) Share of sales

vs. originatorPrice discount

vs. originator*Generic Drug Average ≥75% ≥40% Zarxio (biosimilar Neupogen) ~10% 15% Granix (quasi-biosimilar Neupogen) 5-10% ~11-23% * Public price (e.g., WAC), not including contracted discounts/rebates

Source: Estimates based on publicly disclosed informationOne reason for the difference from generics is that biologic drugs are substantially more complex than small-molecule drugs, as they are derived from living organisms. This greater complexity often creates substantial scientific and manufacturing challenges, and can greatly increase the costs and risks associated with developing and producing biosimilars.

Because it is more difficult to characterize the structure of biologic drugs than chemical drugs, the development and production of biosimilars introduce more variability. This variability between innovator and biosimilar drugs makes it unlikely that the FDA will initially approve many biosimilars as interchangeable with their reference innovator biologic. If this is the case, pharmacies will not be allowed to automatically substitute a biosimilar for the innovator biologic, and payers may be reluctant to push for automatic substitution or implement formulary/managed care mechanisms that encourage switching between the innovator and biosimilar.

In addition, manufacturers will likely use distinct “brand” names for their biosimilars, and may need to invest substantially in marketing and sales to encourage their adoption. In fact, current biosimilars in the United States and Europe are developed and marketed as branded competitors with distinct names.

The FDA is still reviewing how best to address the issue of interchangeability for new biosimilars in the United States. Given the potential safety concerns, it is likely to wait for more information on the experience of the first set of biosimilars before taking a strong stance in favor of interchangeability. This will likely take several years.

As a result of all these factors, we expect biosimilar adoption to be more gradual than has been seen with the rapid shift to generics for many small-molecule drugs. ■

Paul E. Greenberg, Managing Principal

Richard A. Mortimer, Principal

Alan White, Managing Principal

Tamar Sisitsky, Senior AdvisorAdapted from “Can The Life Sciences Industry Bank On Biosimilars?” by Paul E. Greenberg, Tamar Sisitsky, and Richard A. Mortimer, published on Law360.com, April 13, 2016; and “The Potential For Litigation In New Era Of Biosimilars,” by Christian Frois, Richard A. Mortimer, and Alan White, published on Law360.com, September 20, 2016.

-

Uncertainty in the Litigation Landscape for Biosimilars

In recent years, there has been widespread litigation related to intellectual property disputes and alleged antitrust violations surrounding generic entry across a wide range of therapeutic classes. Will the entry of biosimilars in the U.S. lead to a similar wave of related litigation?

A few biosimilar applications have already triggered patent infringement lawsuits. These led to related disputes, such as whether the so-called “patent dance” exchange of information is mandatory and whether the 180-day notice of commercial marketing can be used to further delay the introduction of a competing biosimilar following the expiration of a patent

In addition, entry of biosimilars may result in product safety lawsuits or allegations of improper or misleading promotion. This is made even more likely when the FDA approves the biosimilars for approved indications of the reference brand when the manufacturer did not submit any corresponding trial data, as the FDA did for Zarxio, Inflectra, Erelzi, and Amjevita. This raises the specter of product safety concerns if some patients react differently to the biosimilar than to the reference brand biologic.

Taken together, the complex manufacturing process and array of associated patents, as well as the challenging nature of establishing “similarity” to the reference brand, broaden the potential for a wide range of lawsuits. ■