-

Confusing? Funny? Just Plain Bad? Surveys and Trademark Litigation After Jack Daniel’s

What role will marketing research methods play after the Supreme Court’s ruling in a long-running trademark dispute?

Surveys as Evidence

Surveys have for many years provided empirical evidence in a variety of types of litigation. Their importance was newly emphasized in a recent case decided by the US Supreme Court – Jack Daniel’s Properties, Inc. v. VIP Products LLC – and, in particular, by a concurring opinion by Justice Sonia Sotomayor on the role of surveys in this case and other, similar disputes. The upshot of the concurrence seems to be that surveys must be rigorously designed and executed with care in order to be admissible and carry evidential weight.

The case provides an opportunity to summarize how three types of empirical surveys can shed light on topics that may be important to Jack Daniel’s or future litigation. The first, likelihood of confusion, has long played a leading role in Lanham Act disputes. Because, however, parody products such as the one at issue in Jack Daniel’s intentionally allude to their source products, we also consider two elements that might be useful in gauging trademark dilution: humor and tarnishment.

Bad Spaniels or Bad Parody?

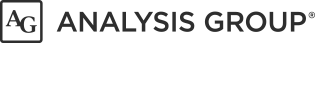

On June 8, 2023, the Supreme Court ruled in the longstanding dispute between whiskey distiller Jack Daniel’s and dog toy manufacturer VIP Products. The case involved VIP Products’ “Bad Spaniels” dog toy, whose square-bottle shape and white-type-on-black-background resembled the iconic sour mash whiskey bottle of Jack Daniel’s. The famous “Old No. 7 Brand Tennessee Sour Mash Whiskey” description was replaced with “The Old No. 2 On Your Tennessee Carpet.”

The distiller sued under the Lanham Act, arguing that the toy both infringed its trademark, because consumers were likely to confuse the two products, and diluted it, because its reputation would be tarnished by the association with defecation. VIP Products countered, and an appeals court held, that the expressive intent of the Bad Spaniels toy shielded it from infringement liability under the First Amendment, and that its parodic intent dispelled the dilution concern.

In a narrowly crafted opinion by Justice Elena Kagan, the court held that when a trademark is used as the source of identification for the derivative work – what the court called using “a trademark as a trademark” – the First Amendment does not provide an automatic defense against infringement claims. Similarly, it also held that the creator of a parody that uses a trademark in this way does not have an inherent defense against dilution claims. It sent the case back for reconsideration.

Using Surveys to Gauge Confusion and Dilution

Justice Sotomayor’s concurrence (which was joined by Justice Samuel Alito) admonished litigants about survey use and admissibility. She advised future courts to “carefully assess the methodology and representativeness of surveys,” and also warned litigants against giving them “uncritical or undue weight.”

One result of the court’s disposition is that when the case comes back to the trial court, empirical questions are likely to be of heightened importance: Is Bad Spaniels likely to cause confusion in the marketplace? Is it a humorous transformation of a well-known trademark, or does it dilute that mark through unpleasant associations?

Likelihood of Confusion

Whether a product is likely to cause confusion about the source of a product in the marketplace is often the key question in a trademark infringement litigation, and it is relevant to trademark dilution as well. Whether and to what extent a product confuses consumers as to its origin is an empirical question, and surveys are widely used to make a case one way or the other. Indeed, an expert for Jack Daniel’s introduced a survey purporting to show that almost 30% of respondents were confused that the Bad Spaniels toy was a Jack Daniel’s product.

One of the most prominent tools for measuring likelihood of confusion is the Eveready-format survey, in which respondents are shown the infringing product and asked a series of questions about it designed to elicit their perception of its manufacturer. In this instance, respondents might be shown a picture of the Bad Spaniels toy and asked questions about who created or manufactured it, or whether it is sponsored by or affiliated with another brand.

Measuring Humor

Parody products can be either infringing or non-infringing, diluting or non-diluting. Since much depends on establishing satirical intent, it may be relevant in future cases for litigants to establish that a product is intended to be humorous, or is perceived by consumers as humorous (or not).

We think that an empirical approach can be of probative value here. While an individual’s sense of humor is clearly subjective, marketing research has suggested that the perception of humor can be measured objectively, since an assessment of the humorous intent of the parody product may well affect its connotations for consumers. As relevant to trademark cases, a humor survey could measure two separate questions:

- Is the at-issue product intended to be humorous or serious?

- Is the product perceived as humorous?

Respondents to such a survey could report their answers on a scale of 1 to 10 to gauge attitudes and reactions.

Tarnishment

Whether a product induces negative associations with its source is often the key question in trademark dilution cases. Does a parody tarnish the brand it’s spoofing by linking it with unpleasant connotations, and do those connotations change consumers’ perception of the brand?

Here again, recent research has proposed a methodology to measure these associations: Consumers are shown the products of a trademarked brand followed by an allegedly tarnishing product. They then respond to questions about brand perceptions about the original. In this case, such a survey might involve consumers being asked questions exploring whether their opinion of Jack Daniel’s products was negatively affected by exposure to Bad Spaniels and its association with dog excrement.

Whatever the ultimate fate of this case, empirical marketing research, properly conceived and implemented, is likely to remain relevant to intellectual property litigation in the years ahead. ■

-

Rene Befurt, Principal

Elizabeth Milsark, Vice PresidentAdapted from Elizabeth Milsark, Rene Befurt, Marie Warchol, and Josh Ng, “Parody and Tarnishment: How Empirical Methods Can Aid Triers of Fact,” IPWatchdog.com (May 19, 2023)

From Forum 2023.